Why do we only talk about ecstasy after someone dies and is that effective in terms of prevention?

Over the years we have had a number of ecstasy-related deaths that made the headlines, some of which have stayed in the public consciousness ever since. Most of these involved young women from 'good' and loving families, each of which appeared to have their whole lives in front of them, but due to a fateful decision to take a pill in search of a good time their future was snatched away from them. There have been other ecstasy-related deaths, however, that did not make the headlines (or even get any media coverage at all in some cases), usually male and most often a little older (although there have been a small number of female ecstasy-related deaths that did not attract media attention) but for the most part, when someone dies after taking ecstasy it generates a huge amount of attention. In fact it is extremely rare to find ecstasy ever really attracting any media coverage unless someone dies - yes, we see law enforcement announcements of large drug busts and drug detection dog operations get picked up by media outlets but I cannot think of one time over the past 20 years when we have seen a story around 'what can we do about ecstasy?' unless prompted by a death ...

Over the years we have had a number of ecstasy-related deaths that made the headlines, some of which have stayed in the public consciousness ever since. Most of these involved young women from 'good' and loving families, each of which appeared to have their whole lives in front of them, but due to a fateful decision to take a pill in search of a good time their future was snatched away from them. There have been other ecstasy-related deaths, however, that did not make the headlines (or even get any media coverage at all in some cases), usually male and most often a little older (although there have been a small number of female ecstasy-related deaths that did not attract media attention) but for the most part, when someone dies after taking ecstasy it generates a huge amount of attention. In fact it is extremely rare to find ecstasy ever really attracting any media coverage unless someone dies - yes, we see law enforcement announcements of large drug busts and drug detection dog operations get picked up by media outlets but I cannot think of one time over the past 20 years when we have seen a story around 'what can we do about ecstasy?' unless prompted by a death ... Let's make it clear, I couldn't care less what an adult wishes to do in a nightclub or a dance event! Ecstasy use is illegal and if you want to take the risk of getting caught and you are totally aware of the harms associated with the drug, that's your business! My concern is the growing number of 15 and 16 year-olds who are writing to me asking me questions about their ecstasy use, some of whom are taking as many as five pills in a night and, not surprisingly, experiencing some significant problems with their drug use. Somehow our prevention measures in this area are not being heeded and it is about time we started to ask ourselves why ...

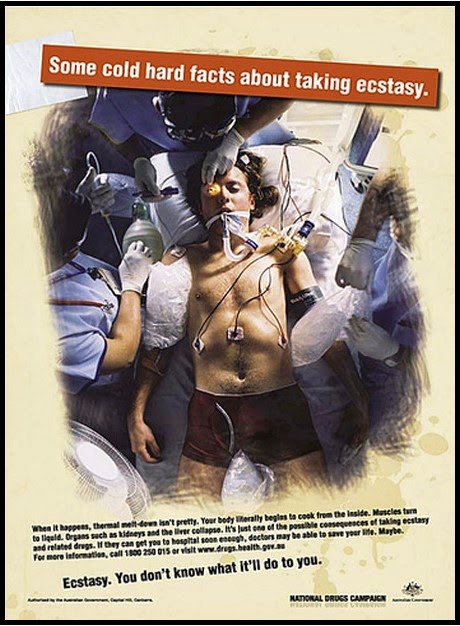

An ecstasy-related death is a rare occurrence, but it does happen. Fortunately, for the vast majority of people who use 'death' is not their reality. Most ecstasy users have a pleasurable effect, that's why they continue to use the drug, and very few people have had direct contact with someone who has died after taking it. This has resulted in the growing belief that ecstasy is harmless, or at least considerably less harmful than a range of other drugs (I have a great problem with how we continue to compare one drug with others in terms of harm - what may be extremely harmful to one person may not be as problematic for another - 'different drugs affect different people in different ways at different times').

When an ecstasy-related death occurs we inevitably get two polarised responses - one from those not involved in the culture who demand that authorities get 'tougher' (conservative columnist Miranda Devine's piece 'We are losing the war on drugs' clearly illustrates this viewpoint) and the other from ecstasy users themselves who try to find a simple explanation as to why the death occurred – usually pushing the point that it couldn't be due to MDMA (what users actually want in their pill), it must have been due to an adulterant of some description (all media outlets ran a story on the possible use of 'purple speaker' pills - interestingly the Daily Telegraph called them 'purple death')!

I believe that the information we should be providing in drug prevention education should focus on what is 'most likely' to happen and be regarded by young people as 'credible'. When I talk about alcohol to school students I always begin my presentation by trying to 'win them over' by highlighting harms associated with alcohol use that they would have already experienced (either through their own drinking or watching or looking after others) - vomiting is my usually way in! Most of them totally relate to vomiting as a very real harm linked to drinking alcohol and once I have them on that, I can pretty well take them anywhere I want! I have gained their trust, they regard me as credible and they are then willing to listen to other information I need to give them ... we need to do the same with other drugs, particularly ecstasy.

As already said, we certainly need to acknowledge the deaths that have occurred. They are tragic stories and can be extremely powerful if used correctly, but let's remember that there are a range of other far more likely harms experienced by ecstasy users that should be discussed that may be regarded as more credible by some:

- feeling sick and vomiting - almost every ecstasy user will tell you that at some point they have taken a pill and become extremely nauseous, many actually vomit. Some users experience this over and over again, each time they take the drug and it is one of the most common reasons why people stop using

- 'comedown' and depression (mental health impacts) - this is without doubt the number one reason why most users stop taking ecstasy and it always surprises me that we don't use this more in our prevention work around the drug. We have a generation of young people who are very conscious of their mental health and we need to do far more about having discussions around the significant impact that an ecstasy comedown can have on school/university, relationships and/or employment

- legal implications – drug detection dogs, roadside drug testing, etc - ecstasy is an illegal drug and that isn't going to change anytime soon! Young people need to know the implications of getting caught with the drug, the difference between 'possession' and 'supply' and how new law enforcement strategies can impact upon their lives

It is difficult to say exactly how many ecstasy-related deaths have occurred in Australia over the years, but when you consider how many people take the drug each weekend, death is not a likely outcome. As already said, when a death is reported users often look for other excuses for the incident – i.e. it couldn't be ecstasy that caused it, it must have been other drugs or the person had a pre-existing condition. In many cases that is true – it is rare for a person to die due to ecstasy poisoning as MDMA (the substance people are actually after in a pill) is not a particularly toxic drug. However, poisonings have occurred (in growing numbers recently) and no matter how much people may want to believe that ecstasy did not cause the death the truth is if the person did not take the drug they would still be alive.

There has been lots of discussion around 'pill testing' (having facilities available for users to test pills before they use them to identify any potential adulterants that are particularly dangerous) since the young woman's death, with some believing that having such a program could have saved her life! I am totally supportive of any strategy that provides more information on what people are taking (I believe the best idea would be to have an 'early warning network' similar to the TEDI program in Europe, which certainly incorporates pill testing) but it is extremely naïve to believe that simply because you know what is in your pill (or at least you know some of what is in it) that means it is safe to take! Ecstasy (or MDMA), like any drug, can attack weaknesses in the user. There have been cases where seemingly perfectly healthy young people use the drug and experience fits, strokes and heart attacks. Many times these are people who have used the drug many times and have never had a bad experience. Put simply there seems to be no rhyme nor reason why these deaths occurred at that particular time. Of course, 'knowledge is power' but it does not inoculate you against all possible harms ...

Ecstasy is not going to go away ... although we do not have data to suggest that we are seeing growing numbers of school students taking the drug, in my experience, those who are using it are much younger, they are doing it regularly and most worryingly, they believe what they are doing is risk-free! We must look at what we are doing around ecstasy prevention, when we are delivering it (we can't do it too early as for most young people it is not yet part of their experience and would be meaningless) and how we can do it better ... Deaths are rare but they do happen and when they do it is an absolute tragedy but focussing solely on these as a deterrent to use is simply not going to work!

Comments

Post a Comment